I often wonder how much people in the world feel the pain and the angst of the world? Do we just go on, oblivious to what is happening, impervious to it all? Or are we like sheep in a fold and just "giving it all to God" in the process? Climatic change, Katrina, economic death knells, post 9-11 fallout, an unnecessary war in the name of Democracy? Is this God's plan? Or does he put us on this planet to work effectively for change, for good, for a harmonious world and not one that kills and hates and eschews common sense?

I often wonder how much people in the world feel the pain and the angst of the world? Do we just go on, oblivious to what is happening, impervious to it all? Or are we like sheep in a fold and just "giving it all to God" in the process? Climatic change, Katrina, economic death knells, post 9-11 fallout, an unnecessary war in the name of Democracy? Is this God's plan? Or does he put us on this planet to work effectively for change, for good, for a harmonious world and not one that kills and hates and eschews common sense? I try not to be political on this blog but to ignore what is going on in this world now and just focus on my house or my boxes of grapes to can or my children and husband seems somehow selfish. But what else can I do? I can't storm Washington, a one-woman banshee of angry, pent-up feelings towards her government. I can write and blog and cook well--that is something. I'm a good wife and mother about half the time--that is also something. I think I'm a good friend (and probably a more authentic friend, at times, than anything else.) But that's the key, isn't it? Authenticity. To ourselves, our mates, our children, our friends. "To thine own self be true."

I try not to be political on this blog but to ignore what is going on in this world now and just focus on my house or my boxes of grapes to can or my children and husband seems somehow selfish. But what else can I do? I can't storm Washington, a one-woman banshee of angry, pent-up feelings towards her government. I can write and blog and cook well--that is something. I'm a good wife and mother about half the time--that is also something. I think I'm a good friend (and probably a more authentic friend, at times, than anything else.) But that's the key, isn't it? Authenticity. To ourselves, our mates, our children, our friends. "To thine own self be true." I can probably strive for better household order and harmony at home. "It starts at home..." Well, if that's the case, why aren't they listening [the family with whom I share a home--and even family members from whom I'm exiled (their choice)--and politicians alike]? I could fold my towels differently or clean the kitchen floor a bit more often. I could allow myself to express anger at the system, within my household or extended family when appropriate. I can nag about everyone's stuff that gets in the way of my stuff or I can invert it and make it all about them, all the time. We can not cage ourselves in and expect that the steam valve won't eventually burst. So we need to let it out and we need to strive for balance. We need to deal with our own stuff and accept responsibility for it, to pick it up and put it away. This I can do.

I can probably strive for better household order and harmony at home. "It starts at home..." Well, if that's the case, why aren't they listening [the family with whom I share a home--and even family members from whom I'm exiled (their choice)--and politicians alike]? I could fold my towels differently or clean the kitchen floor a bit more often. I could allow myself to express anger at the system, within my household or extended family when appropriate. I can nag about everyone's stuff that gets in the way of my stuff or I can invert it and make it all about them, all the time. We can not cage ourselves in and expect that the steam valve won't eventually burst. So we need to let it out and we need to strive for balance. We need to deal with our own stuff and accept responsibility for it, to pick it up and put it away. This I can do. I've decided that what I can do is just to continue to be who I am: a good enough mother, writer, partner-to-my-husband, daughter, friend and not necessarily in that order. I won't tick off the homemaker box because that is not a role I do well. I strive to do that: to keep a house, to tend to healthy meals, to keep up with the laundry. But my mind won't allow it: it has other plans. It's not that I'm against harmonious homemaking, either. In fact, I envy those who can and do. Like exercise and good health, I like to read about it, I like the idea of it but fail miserably in the execution. It is the same with housewivery and yes, often parenting and in my relationships. It is easier to read the recipe or the manual than to implement it. You have to have the right ingredients or tools, the right climate or atmosphere, the right setting. But with most recipes, I usually end up adding my own touches.

I've decided that what I can do is just to continue to be who I am: a good enough mother, writer, partner-to-my-husband, daughter, friend and not necessarily in that order. I won't tick off the homemaker box because that is not a role I do well. I strive to do that: to keep a house, to tend to healthy meals, to keep up with the laundry. But my mind won't allow it: it has other plans. It's not that I'm against harmonious homemaking, either. In fact, I envy those who can and do. Like exercise and good health, I like to read about it, I like the idea of it but fail miserably in the execution. It is the same with housewivery and yes, often parenting and in my relationships. It is easier to read the recipe or the manual than to implement it. You have to have the right ingredients or tools, the right climate or atmosphere, the right setting. But with most recipes, I usually end up adding my own touches.A Mennonite friend of mine says she has better things to be doing than keeping her house clean all the time. Here, here. But her "better things to do" are far more pressing than mine: growing her own food and processing it, helping her husband on their farm. She works hard and in her idle hours she quilts and reads. I'm a cleaner-under-pressure (eg. before entertaining) and I also happen to be blessed with a husband who vacuums better than I could ever do. Another friend, who works equally hard and homeschools (a full time job in itself), and blogs, is happy to be called a Stepford Wife. I don't quite get that as I find it a derogatory term. It is one thing to be proud about the work that we do--in the home or out of it--but it is quite another to embrace your inner robot.

From many of my internet travels I've found that many women today are back in an odd "Cult of Domesticity" that began in the 19th century, an extended period of great change and unrest in the world and modern society. In fact, my self-proclaimed, and proud-of-it, Stepford friend is right in the thick of the movement's modern incarnation that puts God, husband and family first. [I've tried to tell her that, unlike a true Stepford wife, she actually has a brain, heart and soul.] This post-modern cult is one that embraces the feminine and the housekeeper, the pious tender of the hearth and home, like Harriet Beecher Stowe and Catharine Beecher advocated in their pivotal book, The American Woman's Home (1869). The original movement was also a Christian women-driven movement but not one that could be associated with feminism. I find this phenomenon fascinating both in the 19th and 21st centuries, and have studied it endlessly, although I don't necessarily agree with all of its tenets. It is also ironic that Harriet Beecher Stowe, while advocating a harmonious home and hearth for all women, actually had a supportive husband in her writing career (they had seven children and only three lived into adulthood).

From many of my internet travels I've found that many women today are back in an odd "Cult of Domesticity" that began in the 19th century, an extended period of great change and unrest in the world and modern society. In fact, my self-proclaimed, and proud-of-it, Stepford friend is right in the thick of the movement's modern incarnation that puts God, husband and family first. [I've tried to tell her that, unlike a true Stepford wife, she actually has a brain, heart and soul.] This post-modern cult is one that embraces the feminine and the housekeeper, the pious tender of the hearth and home, like Harriet Beecher Stowe and Catharine Beecher advocated in their pivotal book, The American Woman's Home (1869). The original movement was also a Christian women-driven movement but not one that could be associated with feminism. I find this phenomenon fascinating both in the 19th and 21st centuries, and have studied it endlessly, although I don't necessarily agree with all of its tenets. It is also ironic that Harriet Beecher Stowe, while advocating a harmonious home and hearth for all women, actually had a supportive husband in her writing career (they had seven children and only three lived into adulthood). We see the Cult of Domesticity today in magazines like Victoria, for which (ironically) I have written in the past, that give us a hazy filtered view of the world. There is no Dickensian grit here: just the romantic written and photographed longings of a world that probably never was, and a way of removal and refuge from the present. [But, this is true: in the original Victoria Magazine, at least one photographer used to get his diaphanous imagery by smearing Vaseline on the camera lens. All smoke and mirrors, just like the well-staged homes in interior design magazines. You should see the work that goes into making them that way before the cameras arrive. The media tells and shows us what we should see--it was ever thus. So we have to see--and read--through the film and draw our own conclusions.]

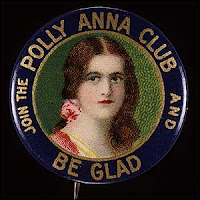

We see the Cult of Domesticity today in magazines like Victoria, for which (ironically) I have written in the past, that give us a hazy filtered view of the world. There is no Dickensian grit here: just the romantic written and photographed longings of a world that probably never was, and a way of removal and refuge from the present. [But, this is true: in the original Victoria Magazine, at least one photographer used to get his diaphanous imagery by smearing Vaseline on the camera lens. All smoke and mirrors, just like the well-staged homes in interior design magazines. You should see the work that goes into making them that way before the cameras arrive. The media tells and shows us what we should see--it was ever thus. So we have to see--and read--through the film and draw our own conclusions.] My maternal grandmother, a brilliant, highly educated woman with the great fortune of a comfortable and loving childhood, was a Pollyanna. Don't get me wrong: I loved the book and the movie and cry buckets every time I see it. I also loved, no adored, my grandmother, especially when I was a child before she became consumed, for the last ten years of her life, by Alzheimer's. That's when the "Glad Game" backfired and she became a different person: depressed, angry, challenging. Grandmother unwittingly played the "Glad Game" for most of her life and I don't doubt that it helped shield her from its realities and get her through some difficult times. But to ignore the grit and the unjust is to also deny and not validate that it is happening. We need to validate our children, our partners, ourselves, our world and not bury our heads in our dough bowls. If only the world were as wonderful as how Pollyanna experienced, we would all be living happily ever after--but it isn't.

My maternal grandmother, a brilliant, highly educated woman with the great fortune of a comfortable and loving childhood, was a Pollyanna. Don't get me wrong: I loved the book and the movie and cry buckets every time I see it. I also loved, no adored, my grandmother, especially when I was a child before she became consumed, for the last ten years of her life, by Alzheimer's. That's when the "Glad Game" backfired and she became a different person: depressed, angry, challenging. Grandmother unwittingly played the "Glad Game" for most of her life and I don't doubt that it helped shield her from its realities and get her through some difficult times. But to ignore the grit and the unjust is to also deny and not validate that it is happening. We need to validate our children, our partners, ourselves, our world and not bury our heads in our dough bowls. If only the world were as wonderful as how Pollyanna experienced, we would all be living happily ever after--but it isn't. What I always connected to with my grandmother, apart from her love and extreme selflessness, were her ideas. She, too, was a frustrated housewife and had other things she'd rather be doing (one was running a farm with her husband, another was teaching, writing and reading). Her intentions were good but she failed in the execution. I'm convinced, like me, she had adult ADD. Her own Victorian mother set a high bar for motherhood and its virtues, for a perfect, seamlessly run home (but she also had household help). Grandmother had too many ideas for one person or lifetime and sadly, she never published a book (but wrote many articles for magazines like New Hampshire Profiles and even won an essay contest with Connecticut Mutual Life on how the individual struggles in the age of automation). So I intend to correct that for my grandmother: to publish some of her words but to also lift up her voice to the world. And to maybe be a better housekeeper for the both of us.

What I always connected to with my grandmother, apart from her love and extreme selflessness, were her ideas. She, too, was a frustrated housewife and had other things she'd rather be doing (one was running a farm with her husband, another was teaching, writing and reading). Her intentions were good but she failed in the execution. I'm convinced, like me, she had adult ADD. Her own Victorian mother set a high bar for motherhood and its virtues, for a perfect, seamlessly run home (but she also had household help). Grandmother had too many ideas for one person or lifetime and sadly, she never published a book (but wrote many articles for magazines like New Hampshire Profiles and even won an essay contest with Connecticut Mutual Life on how the individual struggles in the age of automation). So I intend to correct that for my grandmother: to publish some of her words but to also lift up her voice to the world. And to maybe be a better housekeeper for the both of us.Like my grandparents and my mother and many of my friends who work at or from their homes, I want to be home more than anywhere else (ok, well, maybe excepting Target where I drove for 2 hours yesterday to buy two large glass jars for my pantry--more about that later!) and if not at my home, then in the kitchen of a friend who doesn't care what their house looks like all the time. I've learned to let people see me, dust and all. It's important that our children and partners see our "dust," also, for to cover up and hide it is deceit. Embrace your inner dust, dear reader! Sweep it or vacuum it up, or polish it away, if you must, but acknowledge that it is there and sometimes it is ok to just leave it where it is.

Of course, that said, guess what's on my "to do" list this week? Sort out and clean the brick house (yes, we're still in boxes) for Thursday night Bunco; make grape juice with my friend Anna (so I have to organize the kitchen a bit better first to make room for canning operations); sort out and do laundry piles (that's tonight); cook up a storm (for Bunco); and read and edit a book chapter for a collaborative project (sorry, Nancy, I haven't forgotten that...and please check out her website with essays! Nancy writes novels about hearth and home and the delightful complexities of family). But I wouldn't do it all if I didn't want to do it--and I never complain about it. Procrastinate, yes, but never complain (ok, well, that's not entirely true--I'm remembering that dust remark now). I'll try to save that for our government and failed leadership and things I can not control.

Of course, that said, guess what's on my "to do" list this week? Sort out and clean the brick house (yes, we're still in boxes) for Thursday night Bunco; make grape juice with my friend Anna (so I have to organize the kitchen a bit better first to make room for canning operations); sort out and do laundry piles (that's tonight); cook up a storm (for Bunco); and read and edit a book chapter for a collaborative project (sorry, Nancy, I haven't forgotten that...and please check out her website with essays! Nancy writes novels about hearth and home and the delightful complexities of family). But I wouldn't do it all if I didn't want to do it--and I never complain about it. Procrastinate, yes, but never complain (ok, well, that's not entirely true--I'm remembering that dust remark now). I'll try to save that for our government and failed leadership and things I can not control.A wise elder woman--and we need those in our lives--once said to me, "I always tell my daughters, you can do anything you want in this life, you just can't do it all at once." I try to heed those words and to remember them. I still have books I want to write and publish, I still have children to raise, I still have a house to perpetually get in order. For now, I'm trying to be more in the moment, in the task. Robotic, if you will, but with feeling, like the Shaker motto: "Hands to work, Hearts to God." [And did you know they were an entirely egalitarian order, even believing in a mother deity and a father deity?] I'll tuck into my home even further after some more fall canning and look forward to a more introspective winter of cooking, reading and writing and nestling into the warm embrace of my family--and new friends--in our new land. For now, it's all I can do.

[Image above by Charles Dana Gibson, No Time for Politics, 1910. All other images, except the last two, © Anne Taintor from www.AnneTaintor.com]

2 comments:

Catherine, I didn't realize your grandmother was a writer and produced for NH Profiles as well as articles on how the individual in the age of automation. That is fascinating -- I can't wait to hear more about all of that!

Meanwhile, how about the age of the automaton while we're at it. Surely there's so much to be said about this trend. I'd like to explore this more - the Stepford component, the search for authenticity (or fear of that, perhaps) in our culture and the cult of domesticity and how that applies to these times.

We are just back from a trip and once again I was confronted with all those book stores full of manuals with a target audience of dummies and idiots. They fly off the shelves (in this case, a lot of art for idiots, art history for dummies, etc.). The whole point of art is to provoke a feeling of authenticity on behalf of the viewer, but people would rather think they are an idiot and need to be told what they like.

Our society is addicted to mediocrity and now it's vogue to be off the hook for speaking out or playing a role because it's okay to just want to be dumb. Hey, I'm an idiot. How easy is that? More and more people seek others to tell them what to do.

This was a great blog, Catherine -- so thought-provoking. Thank you!

Edie

The other thing, I think, Catherine, is that for me, and I think many women, our vision of what home life ought to be is actually predicated on the presence of another pair of hands. I realized a number of years ago that what I based my idea of a proper household looked like was British novels: with nannies and dailies.

I was at the time smocking dresses and knitting sweaters and baking bread and teaching school and being miserable because the house didn't look as I thought it should. I suddenly realized that if I had a nanny I wouldn't expect her to knit for the children; and if I had a cook, she wouldn't be cleaning house; and if I had a tweeny she wouldn't be baking bread. No wonder one little woman was always behind!

Post a Comment